In a previous article on motivation and grit in learning experience design, we described grit as the pursuit of one’s passion, with ‘consistent interest and sustained effort over a long period of time’ (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) and looked at its role in ensuring learners are fully engaged and motivated throughout a learning experience. This idea of staying motivated throughout a learning experience and sustained engagement in practice activities is key to developing new skills, competencies and behaviours.

So, how can we create opportunities for learners to put their new or emerging skills into practice by directing that long period of time using deliberate practice? Thankfully there’s some research we can look to to help us create relevant, challenging opportunities that allow learners to practice new skills.

Deliberate practice is a concept that focuses on improving skills and extending the reach and range of those skills. It refers to ‘intentional and sustained efforts to work on developing new competencies. It’s not just practising the same repetitive exercises over and over, but rather, it’s the steady improvement and extension of a range of skills’ (Ericsson, Prietula & Cokely, 2007).

In 1993, psychologist K. Anders Ericsson became fundamental in establishing the role of practice as it shapes experts, specifically, and originally, in the field of music. While many people believe that talent is essential to becoming a professional instrumental musician, deliberate practice seeks to show that hard work and focussed training play a much larger role in creating experts of all fields.

His work inspired Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers, which popularised the opinion that simply working at something for 10,000 hours can turn you into an expert. But deliberate practice is much more about what you do with the time you spend practising. As it turns out, there is no amount of time that you can put into acquiring a skill that will automatically make you an expert. In fact, it’s possible to engage in solitary practice without improving your performance (McPherson and Renwick, 2001).

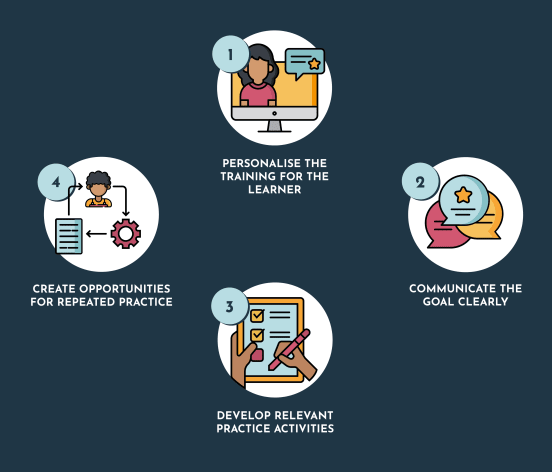

In Ericsson’s original work with musicians there were four criteria which defined deliberate practice. The first is that deliberate practice should involve individualised training of a learner by a well-qualified teacher. Secondly, the teacher communicates the goal to be achieved by the learner by showing them what success looks like, allowing them to evaluate for themselves if they are meeting the standard during their solo practice time, and so that they can effectively learn to coach themselves and know if or when they are improving.

The third criterion is that the teacher describes practice activities for the learner to work on in order to develop their skills. And lastly, the learner attempts the activities repeatedly as they work on achieving the goal. The learner also receives feedback during the regular solitary practice with the teacher, who would then adapt the practice activities for the following lesson. Thereafter the teacher sets new goals, and so the process continues.

While deliberate practice has been well-researched, many of us find ourselves without an expert teacher at arm’s reach. So, in 2016, Ericsson and Pool proposed the term purposeful practice for individualised practice activities that a learner engages in in order to improve their performance without the guidance of an expert teacher. Purposeful practice can be duplicated in other domains and can help structure your self-directed learning, making it a useful way to think about achieving personal goals, or attempting to improve your skills through a self-directed learning programme. For digital learning designers attempting to create online learning experiences that are scalable and sustainable, creating opportunities for purposeful practice is key to the success of the learning programme.

Here are four tips for designing learning experiences with purposeful practice opportunities.

Start by setting clear objectives and specific goals and criteria which learners can measure their success and progress against. These might be in the form of learning outcomes or by demonstrating what success or proficiency in a certain competence or skill looks like. By emphasising what a learner will be able to do at the end of a learning experience, and the new skills they will be able to apply, you’re creating an opportunity for learners to visualise their success up front.

Knowing what to aim for is key for learners to achieve their outcomes. To do this, you should also gather baseline data and include frequent opportunities for learners to reflect on whether they are meeting the learning goals. This can be achieved through regular assessments or surveys, structured practice activities or reflective journal prompts.

Once you’ve established challenging, yet realistic goals, providing the framework for learners to look to the next level of performance will help them to continue striving for improvement. This is a part of having a growth mindset, where achieving one level of success is not the main goal. Instead, the learner always has their sights on what the next level of success would be (Dweck, 2015). Developing this degree of self-awareness during the learning experience can be achieved in part by using model answers, practice scenarios, or explainer videos.

In addition, including rubrics with structured and detailed success criteria per level will highlight to learners what varying versions of successful application of a skill can look like. Providing exemplars to help narrate or model what success looks like before a learner begins to practise a new skill or behaviour or apply new knowledge helps them to reflect on their current and future level of competence.

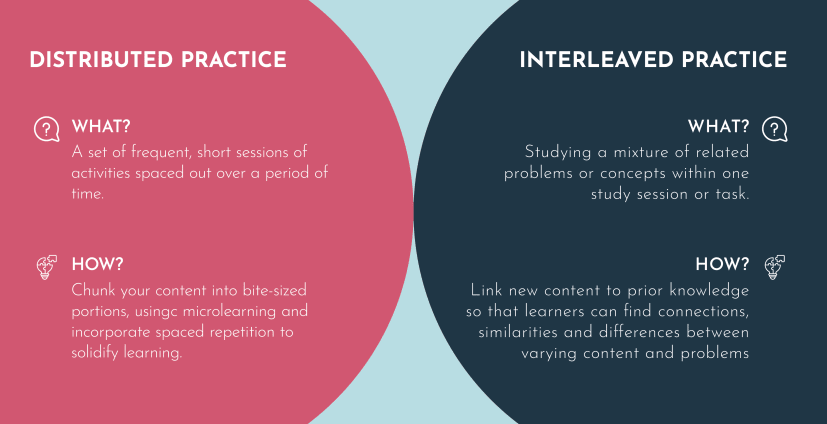

An important part of purposeful practice is for learners to apply themselves in a structured way by engaging in focussed and targeted practice. According to Bromley (2014), there are two kinds of practice which increase student success: distributed practice and interleaved practice.

When these activities are challenging, but attainable, the learner is able to perform optimally. Encourage them to engage in the learning content by scaffolding activities, building on their skills throughout the learning programme.

Provide clear instructions for completing different tasks, including how much time should be spent on each activity, and share tips up front for moving through the learning content in a meaningful way. Where possible, create a learning plan or schedule that learners can adapt and follow so that they can implement and apply their learning effectively.

Provide opportunities for learners to regularly evaluate their progress. Compare their findings with the data collected at the beginning of the learning programme in order to determine whether there is a change in behaviour or competences and what can be improved going forward.

If your course allows, provide individualised feedback, or at the very least, suggested or model answers for different activities and tasks. Feedback should also be continuous and focus on the effort the learner has put into the learning process, rather than on the assessment or grade itself. This gives learners another opportunity to evaluate their own progress, even if you can’t provide that detail at an individual level.

Peer learning is another way to give and receive feedback, so have learners partner up on activities or share their ideas in a community discussion forum. The more immediate the feedback, the better, so where you can’t provide this yourself as a course instructor, have the learners learn from each other.

Human beings like to look up to experts like superstars and we like to believe that we ourselves can do better, achieve more and reach our potential. Using deliberate practice in learning experience design increases the average learner’s self-awareness and means the learner not only practises deliberately but it makes the learner think deliberately. Using deliberate practice methods means improving the skills the learner already has and extending the reach and range of their skills.

There are many elements of deliberate practice that have and will continue to be studied as it applies to learning success, and particularly in a digital realm. As you design learning experiences, implementing small, practical ways to include deliberate practice to turn your learners into experts will ensure you continuously put your learners at the centre of your design.

REFERENCES

Christensen, U. J. (2020) Why Corporate Learning Needs Ericsson’s Deliberate Practice More Than Ever. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ulrikjuulchristensen/2020/06/22/why-corporate-learning-needs-ericssons-deliberate-practice-more-than-ever/?sh=3275ede87e1e

Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92(6), pp. 1087–1101.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review. 100(3), pp. 363-406.

Ericsson, A.K., Prietula, M.J., Cokely, E.T. (2007). The Making of an Expert. Available at: https://hbr.org/2007/07/the-making-of-an-expert

Ericsson, K. A. & Harwell, K. W. (2019). Deliberate Practice and Proposed Limits on the Effects of Practice on the Acquisition of Expert Performance: Why the Original Definition Matters and Recommendations for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 10: 2396. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02396/full

McClendon, C.,Massey Neugebauer, R. & King, A. (2017). Grit, Growth Mindset and Deliberate Practice in Online Learning. Journal of Instructional Research. 6(1027), pp. 8 - 17.